Hollow Man

American Cinematographer, Aug. 2000

Transparent Camera Moves

By Les Paul Robley

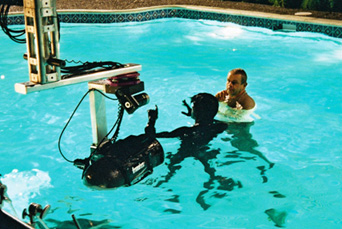

General Lift provided the production with a fully configured Aquaflex motion-control rig. Here, the unit's Hydroflex camera housing is fully submerged in a swimming pool, which was part of a set built within the enormous Stage 12 on the Sony Pictures lot.

Motion-control" is a phrase that strikes fear and loathing in the hearts of even the most seasoned film crews. This painstaking technique traditionally takes longer than normal camera setups and has a greater degree of Murphy's Law built in, despite the superior accuracy one gets from controlled movement and perfect repeatability.

Hollow Man promises incredible invisible effects unlike any (un)seen before. In collaboration with visual-effects supervisor Scott Anderson and director of photography Jost Vacano, ASC, BVK, director Paul Verhoeven worked to achieve motion-control that would not reveal itself as motion-control. The equipment needed to be quick and easy to set up and versatile enough to be effortlessly re-rigged as shots were modified on set. Most importantly, the film needed to took as though it had been shot with a free-moving camera.

"There was so much motion-control on the first and second units of Hollow Man that I made a point early on to try and have the equipment accepted by all departments as standard production gear," recalls motion-control operator Eric Pascarelli. "I have often encountered an 'Us vs. Them' mentality toward motion-control on live-action sets, and I wanted to avoid it on such a long project."

Sony Pictures Imageworks' silent, servo-driven Stealth Dolly was used for the entire nine-month shoot, along with several special rigs made by General Lift in El Segundo, California. The motion-control moves were performed by each of the camera crew members seamlessly - dolly grip Mike Connor controlling the Stealth Dolly; Leo Behar operating the boom elevation axis; operators Tom Yatsko (first unit) or Phil Forester (second unit) panning and tilting the camera using remote wheels or an encoded Sachtler or O'Connor fluid bead; and first assistants Greg Irwin (first unit) and Lauren Yaconelli (second unit) pulling focus in real time. Using the updated Kuper RTMC 130 software, all of this information was gathered by Pascarelli as if he were a data sponge.

William Devane, Kevin Bacon, (in black) and RotoFlex head with Hydroflex housing.

'Just because Bacon was invisible in this underwater scene where he struggles with a government agent (William Devane) doesn't mean he got the day off... In these scenes, Bacon wore a black suit, wig, and makeup, so he could be painted out of the frame, and replaced with CG models later.'

For scenes involving Kevin Bacon's invisibility, motion-control was required because his "hero" take would be immediately followed by a "clean-plate" pass to provide the background information that was covered by the actor. Extra passes of the same shot might be made for other elements, such as smoke and fire, or splashes, bubbles and drips in the wet scenes. The track, boom, pan, tilt and focus axes were played back together for each of these clean passes without anyone in the plate so that all camera movement would repeat precisely for the digital compositing stage later.

Bob Sterry of CompMagic, one of the visual-effects video-assist operators, explains, "We triggered the mo-co with time code using Kuper's Start TCode Trigger feature, then played back the live-action passes with a simple video dissolve against the clean passes to make sure the moves lined up precisely."

Hollow Man marked the first time a fully immersed, underwater, motion-control camera rig was used in a feature film. The film's ambitious shots meant that the rig needed to have a great range of motion. The entire pan/tilt head and all cabling had to be waterproofed so that the rig could be submerged as far as necessary. The rig also had to facilitate shots beginning underwater and breaking the surface. It needed to be very fast and powerful so it could handle sudden changes in buoyancy.

"Hollow Man's use of wet motion-control, or what I called hydrodynamic motion-control, was required for two sequences," explains Joe Lewis, owner of General Lift. "One was a swimming pool at a suburban home in Washington, D.C.; the other involved the secret, subterranean lab corridors beneath the city. [After meeting with the visual effects producers], we came up with a set of specifications, and in December of that year Tippett Studios took over these sequences.

"For the pool scenes, we were able to utilize different components from our stable of systems," Lewis details. "The basic system consisted of 24 feet of narrow-gauge Tiffen Motion-Control Track, which ran parallel to the pool's edge. Atop this was a tower with six feet of vertical travel mounted on a JetRail dolly, a modified GenuFlex boom arm that could extend manually out over the pool, and a custom RotoFlex Pan & Tilt head with waterproof stepper motors. To this we fabricated a precision mounting bracket with quick-release pins to attach the HydroFlex housing for an Arriflex 435 camera. We modified one of our stepper-motor focus brackets to mount to points supplied on the Arri 435."

The action in the pool is the violent drowning of a character by the invisible Bacon. The system needed to be versatile enough to travel with the action as it moved from above to below the water's surface. As with the dry motion-control, all axes were controlled with encoders by the same crew of operators. Pascarelli handled all of the data-recording and system-playback functions using the same Kuper software.

"The underwater motion-control shoot took place almost a year into the schedule, and it had to work the same way as everything that preceded it," Pascarelli points out. "We had achieved a certain pace and method of working that needed to be maintained. The camera and housing were removable by registered quick releases so that the film mags could be changed between passes with perfect repeatability. An underwater assistant would hand the camera off to a dry assistant, who would then reload or change lenses, and we'd be on our way."

Adds Lewis, "We rigged an underwater lipstick video camera that allowed us to check our 'home' reference marks for the immersed axes between takes. This helped streamline the production. Even the ubiquitous bloop light or frame marker had to be housed inside a waterproof case to indicate the first frame of the move for later line-up during the compositing stage. The entire system was isolated electrically on its own Shock-Block GFI [ground fault interruptor] box. This sequence and the rain corridor shots were daunting, in that the GFI boxes would shut down immediately if any problem was detected."

The underwater camera consisted of an Arri 435 equipped with back-slung magazines designed to fit within the HydroFlex housing. The rain-corridor camera was a modified Fries Mitchell 35R3. Lenses were all Zeiss T2.1s, and the film stocks were Kodak's Vision 200T 5274 and SFX 200T.

The lab rain-corridor shots, in which the invisible man's form is revealed by water running off of him, utilized a slightly modified JetRail dolly, a "water-hardened" Extendo-Matic elevation rig and a modified RotoFlex Pan & Tilt head. A series of U-Bangis were fabricated to allow the camera to be placed in a variety of positions. A reflexed Fries Mitchell camera was placed in a HydroFlex Splash Bag with twin compressed air nozzles that blasted off the water as it hit the front port. By experimenting, the camera crew found that aiming the nozzles asymmetrically with an ongoing application of Rain-X was effective in keeping the heavy deluge off the glass. The JetRail dolly ran on standard Peterson/Holt I-Beam track with a belt that provided a non-slip drive. For sync sound, the dolly was not as quiet as a complete frictiondriven servo system, but given all of the noisy water effects, this was not a problem.

"We were able to move the system quite quickly through the water with no repeatability problems, and we could do pretty fast whip-pans as well," Lewis notes. "It worked better than I ever expected."